H. Beau Altman, Ph.D., founder of Flight Attendant and Crew Training Seminars (FACTS) and a 40+-year aviation safety innovator, says that many, if not most, business aircraft travelers ardently resist undergoing basic cabin safety training. The typical showstopper is the 3-6-hr. time commitment required for classroom instruction and structured practical drills. Notably, 90% or more, of all business aircraft operators do not have professional flight attendants aboard. Thus, the passengers must fend for themselves in the event of mishaps.

Altman uses a simple, quick and compelling test to convince business aircraft passengers that they’re unlikely to survive the most common emergencies without formal training. “Give me 10 min. of your time,” he asks potential participants. He seats each of those who consent in a chair and with a life vest discretely placed in a pouch underneath. He then informs them that they’re aboard an aircraft that’s about to ditch in deep water.

“You have 30 sec. to find your life vest, put it on and attach the chest straps,” Altman says, then: “Go!” At that point, he turns out all lights to create a pitch dark simulated cabin environment.

In reality, he waits a full minute to provide ample time for passengers to don the life vests. After 60 sec., he flicks on the lights and announces, “Time’s up!”

After three decades of these demonstrations, he’s seen very few business aircraft travelers who complete the life vest donning drill successfully on the first attempt. That exercise, along with some other basic demonstrations, has convinced several skeptics of the need to invest their time in formal cabin survival training. Altman says National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) data show that up to 80% of all aircraft accidents are survivable, if occupants are proficient in emergency procedures.

Effective retention of cabin survival skills is directly dependent on the type of learning experience, says Altman. People retain 10% of what they’ve read, 20% of what they’ve heard in a lecture, 30% of what they’ve seen in a slideshow and 50% of what they’ve seen and heard in a demonstration.

Ground school, including both passive demonstration and active discussion elements, boosts retention to 70%. But if you involve passengers in active participation sessions, retention goes up as high as 90%, assuming instructors throw in a few curveballs such as a life vest or life raft that won’t inflate properly, a cabin exit that gets blocked or an emergency O2 mask that doesn’t drop from the ceiling compartment. “What’s your Plan B,” he might ask. Follow-on queries include: Do you know how to use garments or plastic trash bags as impromptu life jackets? Do you know where all the exits are and how to find them in the dark? Do you know where spare emergency O2 masks might be available?

While participation training requires the most time investment and yields the highest benefits to passengers, Altman recognizes the value of introducing basic familiarization documents and working toward more intensive training systems as passengers learn more about cabin safety.

The Basics — The Pictogram Safety Briefing Card

In 1972, Altman co-designed the first non-verbal, pictogram intensive passenger safety briefing card for the aviation industry. It became the basis for his 1975 doctoral dissertation, “The Use of Pictorial Materials in Aircraft Passenger Safety,” at Southern California’s Claremont Graduate University. While the dissertation was relatively short (87 pages) by academic standards, it was endorsed almost immediately by aviation industry experts for its cost-effective approach to enhancing passenger safety and its commercial value to the aviation community.

a speedy emergency egress with no help from a flight attendant. Credit: H. Beau Altman, PhD

The value of his pictogram safety briefing cards became all too vivid on March 27, 1977 when KLM 4805, a Boeing 747, began its takeoff roll in dense fog at the Tenerife North Airport. Seconds later, it would crash into Pan American 1736, another Boeing 747, still was on the same runway and about to turn onto an adjacent taxiway. The ensuing crash killed 583 passengers and crewmembers. Only 61 people survived.

One of the passengers who made it through the mayhem emerged from the emergency exit of the Pan Am jumbo still clutching a pictogram safety briefing card. He and his wife, who also survived, told a television news crew on scene that both had studied the briefing card before the flight, so they knew precisely how to find, open and escape through the aircraft’s emergency exits.

When people learned Altman’s company had designed the innovative briefing cards for Pan Am, the firm became swamped with new orders from both airlines and business aircraft operators.

Many new business aircraft manufacturers make available pictogram passenger safety briefing cards to their customers. But these often vanish from the aircraft as they change owners over their service lives.

Replacement briefing cards may be purchased from several firms. However, the ones that show the safety features of the specific aircraft you fly are more useful than generic safety information cards. The best examples illustrate how to fasten and release safety belts, proper brace positions for high deceleration stops, location and operation of normal and emergency exits, emergency egress procedures, use of drop-down oxygen masks, how to don life vests and gain access to life rafts and where to find, plus how to use, fire extinguishers on specific models of aircraft.

Video Brief

Years ago, Altman produced a passenger briefing VHS video for Olan Mills’ flight department in Chattanooga, Tennessee, a firm that operated Falcon 10 s.n. 34 from 1975 to 2002. Featuring Olan Mill’s own Falcon pilots and usual business aircraft travelers, the video showed where passengers could properly store baggage and carry-on luggage for takeoff and landing, how to fasten and unfasten passenger seat belts, the proper seat-track and seat-back positions for landing and takeoff, use of emergency oxygen masks, response to emergency commands from pilots and all other emergency response actions for which passengers need to be prepared.

In the training video, the Olan Mills passengers actually opened both the main clam-shell entry door and right-side emergency exit. One of the passengers demonstrated how to remove the emergency exit from inside the cabin, turn it on edge and then throw it out over the wing. Not shown in the video, the exit was carefully caught by a maintenance technician outside the aircraft so that the exit hatch wouldn’t crash into the wing skin.

Each of the three passengers on camera then crawled through the emergency exit, stood atop the wing and slid safely off the leading edge, no doubt wearing soft soled shoes that wouldn’t mar the paint during video production. A narrator instructed the passengers to run clear of the aircraft, move away from the runway or taxiway and remain there until told where to go by airport personnel or flight crewmembers.

After the project was completed, Olan Mills required its passengers to watch and discuss the video, resulting in up to 50-70% retained learning, according to Altman. Lessons learned on the instructional tape could be reinforced by placing pictogram passenger safety briefing cards aboard the aircraft.

In 2002, Olan Mills sold the aircraft to an owner/operator in Newport Beach, California, and it was based mainly at Orange County — John Wayne Airport for the next 5 yr. Notably, when we last flew this aircraft 15+ yr. ago with the second owner, both the original briefing cards and video had long since vanished. We, as the flight crew, had to brief passengers verbally with no visual aids, perhaps slashing passengers’ comprehension of emergency procedures by one-half to two-thirds, or more.

This is typical for many operators of older business aircraft. The pilots are required to provide safety briefings with no pictogram briefing cards or other visual aids.

Today, it’s considerably easier to recreate and to make available cabin emergency training videos to passengers because of the ready availability of computer-generated graphics and web video. Operators don’t have to rely on the availability of VHS tape and players, along with TV sets. Passengers can log into a secure website and view training videos at their convenience on laptop screens or personal electronic devices. In doing so, when they arrive at the boarding steps, they’re considerably better prepared for contingencies than if they just listen to an oral briefing.

Aircare FACTS Training

In 1998, Altman sold FACTS to Aircare International, a firm that had previously specialized in emergency medical training for cabin crews and pilots. Aircare enhanced and expanded the program over the next two decades, upgrading the FACTS motion-based simulators, adding new features, such as reduced oxygen breathing device hypoxia training, inflight fire fighting and water immersion dunkers that flip occupants upside down.

While those training programs are aimed primary toward cabin and cockpit crews, Aircare also offers “executive frequent flying” training that is especially valuable for business aircraft operators who don’t employ flight attendants.

Many corporate aircraft travelers do not recognize that, in the absence of cabin crewmembers, they may not react to the initial signs of an impending aircraft emergency and respond quickly and appropriately to assure their survival.

Most FACTS programs include at least 3 hr. of classroom training in the morning and 3 hr. of practical training in the afternoon. This is a substantial time investment for many executive travelers, so relatively few business aircraft passengers have undergone the training. But only 10% of all FAR Part 91 business aircraft pilots also have attended FACTS or an equivalent program, which is to say 90% of them have not experienced a simulated crash, emergency egress, water survival training or actual firefighting. As such, they may be ill-prepared to assist passengers in emergencies even though they are proficient in handling all FAA-mandated aircraft emergencies as demonstrated during periodic FAR Part 142 simulator training.

Most business aircraft passengers, as well as flight crews, never have had to find their way from seats to emergency exits in a dark, smoke-filled cabin simulator. They’ve never been challenged to find an alternate exit in case the primary one is blocked. They’ve never had to follow a voice in the darkness from an airport rescue crewmember on top of a wing yelling “Over here! Over here!” through an emergency exit that’s been opened from the outside, says Altman. They’ve never donned a life vest or used an oral inflation tube on a life vest because the compressed air bottle didn’t function and never deployed and inflated a life raft.

Passengers seldom are taught that a life raft can be converted into an effective weather shelter for long term survival on dry land. They don’t know how to use a signal mirror to send an SOS to a passing aircraft or rescue helicopter. They’ve never used a handheld signal flare or shot a flare gun. They’ve never fought a fire using a hand-held fire extinguisher. And they’re ill-prepared to cope with a personal electronics device lithium ion battery fire inside the cabin.

On-Site Training

To conserve their passengers’ time, a few business aircraft operators opt to conduct emergency procedures ground school and practice exercises at their own facilities. But former business aircraft operator Tennant Corp. contracted with Aircare FACTS to provide on-site classroom training for its executive travelers during morning sessions.

In that on-site program, flight physiology was a major focus. It was assumed that many passengers, for instance, may not have appreciated that in the event of a sudden cabin decompression, the time of useful consciousness without emergency oxygen is extremely brief. Or they might not have understood why it’s so vital to don their own oxygen masks first before attempting to help others.

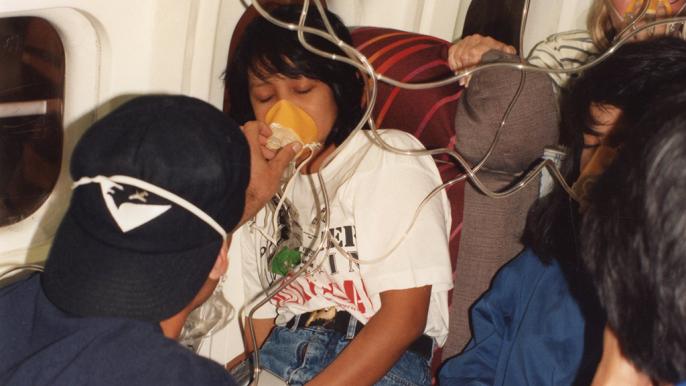

Former flight department manager Pat Gordon then used company aircraft for many practical exercises, including emergency egress drills, donning life vests and use of drop down oxygen masks, during afternoon training sessions.

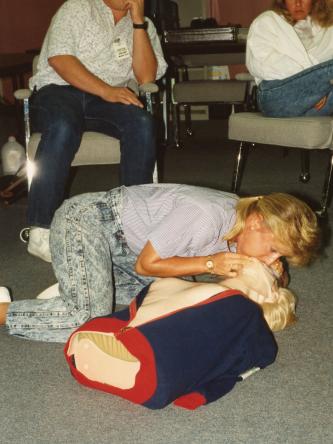

Now, such practical on-site training usually includes a first aid refresher and CPR. Written tests often are included with ground schools, enabling passengers to evaluate their own learning progress in preparing for emergencies.

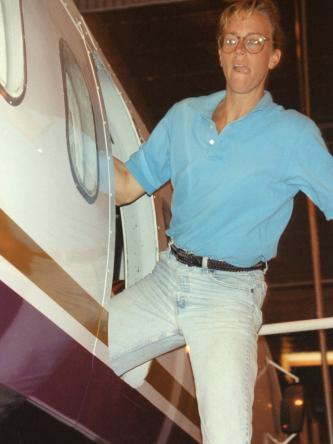

For onboard emergency drills, using the actual company aircraft on which passengers fly boosts the value of cabin emergency training because they are familiar with the cabin configuration, floor plan, interior furnishings and proximity of emergency equipment aboard. Drills usually are conducted inside hangars because lights can be dimmed and hangar windows can be shaded to provide darkness, thus simulating night emergencies.

Passengers often are surprised at the weight and heft of emergency exits, the difficulty of tossing them out of the aircraft and the distance between the bottom of the emergency exit and the top of the wing. On some business aircraft, it’s difficult for passengers to move through an emergency exit without injuring themselves. Cuts, bruises and sprains may be expected for those who have not practiced escaping through such exits.

Once they’re outside the aircraft and atop the wing, it’s essential for passengers to know how to help others escape, how to aid others in moving to the edge of the wing and how to slide to the ground without injury.

The passenger resistance to such classroom and aircraft cabin emergency training can increase individuals ascend the corporate ladder, but Gordon had the full support of Tennant’s chairman, thus who made the training for passengers mandatory. Non-participants were added to Tennant’s “No Fly List”.

Unfortunately, Altman says, in today’s high-pressure, high-productivity business environment, few business aircraft operating companies seem to find the time for hands-on cabin emergency procedures training for passengers.

And excepting large cabin aircraft operations, including those of Part 135 charter companies and Part 91K fractional ownership providers, flight attendants are becoming increasingly rare aboard business aircraft. The main function of cabin crew is to ensure the safety of passengers. Without flight attendants, it’s up to passengers to secure their own survival in the event of aircraft mishaps. As Altman has repeatedly demonstrated in drills, the majority of untrained passengers can’t perform up to snuff when confronted with the most common cabin emergencies.

Altman has started a new program called Ascert, short for aviation safety, crisis and emergency response training. One of its key principles is active participation in cabin safety on the part of business aircraft passengers. They become part of a crew/passenger resource management team whose members are trained to recognize unusual odors, in what to do when an oxygen mask fails to deploy, and how to assist others outside the aircraft in the event of a forced landing or ditching, among many other emergencies.

“Safety is freedom from unacceptable risk,” says Altman. “Survival depends on passenger ‘response-ability’.”

Even so, many executive travelers often are reluctant to buy into the concept of crew/passenger resource management, becoming part of a team effort that supports the flight department’s safety management system. And yet active participation by passengers can be vital to their developing situational awareness, thereby enhancing their perception, comprehension and prediction of impending cabin emergencies and forming survival strategies.

Self-preservation instinct, however, is a powerful motivator. Once passengers grasp that should a mishap occur, they alone may be responsible for their survival, as well as that of others aboard the aircraft, they may convince themselves to learn all about cabin safety.