Visual guidance lighting systems

As is common in limited investigations, NTSB investigators did not travel to the scene of the hard landing at FRG. An FAA inspector from the Farmingdale FSDO responded to the accident scene, took photos and documented the wreckage. The FAA inspector was a party to the investigation, along with the operator, Talon Air, and the engine manufacturer, Honeywell. Talon Air’s director of operations completed the NTSB form 6120, from which some of the final report’s details were drawn.

The Raytheon Hawker 800XP, manufactured in 2001, had accumulated 12,731.5 hr. at the time of the accident. Data downloaded from the engine’s digital electronic control units showed there were no engine malfunctions, and the NTSB accepted the statements from Talon Air and the crew that there were no mechanical issues with the airplane.

The airplane’s cockpit voice recorder (CVR) was recovered and sent to the NTSB’s vehicle recorder lab in Washington, D.C.. The FAA inspector and a Talon Air captain, along with the NTSB’s recorder specialist, formed a CVR group and auditioned the recording. The quality of the recording was excellent. The investigator in charge decided that only 7 min. of the 30 min. recording should be transcribed. The remainder of the recording was summarized by the recorder specialist.

The aircraft was not equipped with a flight data recorder (FDR) and ADS-B surveillance data was not used in the investigation. The facts in the case seemed pretty clear without them, except for the movement of the pilot yokes on the attempted go around.

The 37-year-old captain held multi-engine ATP and CFII certificates and had accumulated 4,188 total flight hr., 2,060 of which were in the Hawker jet. He told investigators that most of his time was in the Hawker 900, with about 100-250 hr. in the 800 model. He said he had logged about 2,300-2,400 hr. in Part 135 operations. There were no restrictions or limitations on his first-class medical certificate.

The captain said he completed his pilot training in 2006 and was hired by Talon Air in May 2019. His employment in the interim was not stated. He was not asked about his experience or training in flying approaches below Category I minimums.

The first officer was 63 and held an ATP and a Hawker 800/900 type rating. There were no limitations on his first-class medical certificate. He had about 10,000 total flight hr. and reported 4,100 hr. on the Hawker, of which 2,500 was in the 800 model. He had transferred to Talon Air from another company one month before the accident and had only been line flying with Talon for two weeks.

The two pilots had not flown together before the accident trip, but both told investigators they worked together well. Both reported being healthy and well rested. Both had flown the ILS Runway 14 approach many times and both had received company training on rejected landings from 50 ft. and missed approaches.

A note on the FRG ILS-14 approach plate says, “autopilot coupled approach NA below 310.” The CVR showed that the FO left the autopilot engaged to about 50 ft.

Meaning of 14 CFR 91.175

Every instrument-rated pilot has had to learn what’s said in 14 CFR 91.175, “Takeoff and landing under IFR.” Unlike 14 CFR 135.225, which refers to Part 135 operations; and 14 CFR 121.651, which refers to airline operations, the Part 91 regulation does not prohibit pilots from beginning an instrument approach when the ceiling and visibility are below prescribed minimums. When you are operating under Part 91, you are allowed to “look and see” if conditions are good enough to land.

That doesn’t mean you can land. You still must comply with the prescribed decision height/decision altitude (DH/DA) or minimum descent altitude (MDA), and you can’t go below it until you meet three criteria: you must be able to descend at a normal rate (not dive at the runway); the flight visibility must be at least as good as the minimums for the procedure; and you have to clearly see at least one of 10 specified elements of the runway environment.

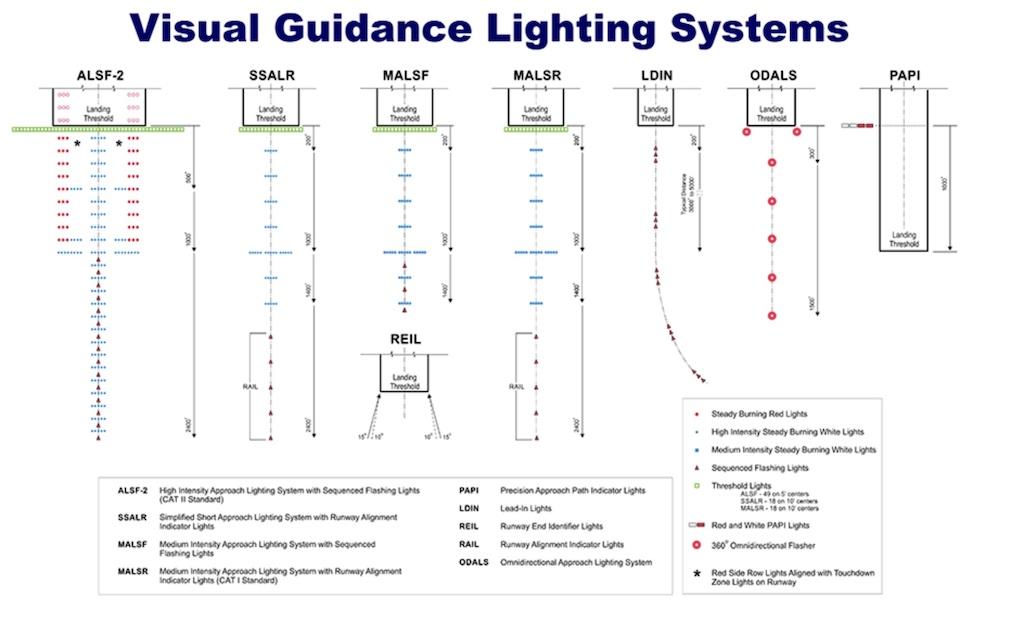

One of the 10 specified elements is the approach lights. Just seeing approach lights alone is not good enough to descend below 100 ft. To do that you have to see red terminating bars or red side row bars, and they only apply where there are ALSF 1 or 2 light arrays.

When you are approaching a runway that doesn’t have an ALSF 1 or 2 approach lighting system and you are relying only on the lights, you can’t go below 100 ft. You must find one of the other nine elements to descend below the DA or MDA.

It is possible for pilots operating under Parts 135 or 121 to continue an approach when ceiling or visibility has fallen below minimums. If you have already begun the final approach segment when you hear the new, lower weather report, you can continue to the DA or MDA. At that point, you must comply with the same three conditions that apply to Part 91.

In Below Minimums Hard Landing, Part 3, we offer conclusions and comments.

Cause & Circumstance:Below Minimums Hard Landing, Part 1: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/cause-…