SMS Unplugged: Reporting And Next Steps

Implementing a safety management system (SMS) can be simplified. To see how, see the first part of this article series here.

Once just culture is in place, the reporting system can be used by the employees with confidence. One observation is that the mechanics of the reporting system can be started almost overnight, but the trust associated with confidential reports and just culture (JC) take much longer, sometimes years. Patience is required when it comes to some forms of reports. For example, early on, the reports may be limited to “non-jeopardy” reports where the reporter was not at fault. A bird strike is a good example. It may take longer for people to open up completely and report mistakes.

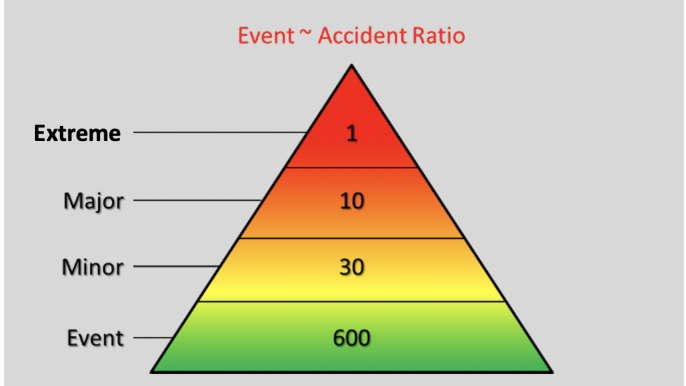

So, why the interest in these reports in the first place? The reason is based on the Loss-Ratio Triangle (above). Consider this situation. There is an electrical cord stretched across a hallway. Now, picture a person tripping over that cord. In this case, nothing happens. The person might look back and think that the cord across the hallway is probably not a good idea. The Loss-Ratio says this basic event happens 600 times. But in another 30 events there was some minor injury or damage, such as pulling a computer off the table and breaking it. In 10 more cases there was major damage or injury, such as a broken hand or arm. And in one of the cases, there was an extremely serious outcome. In this case it might be an elderly person or someone who has been drinking who trips over the cord and kills themself.

What is the hazard? The cord across the hallway. What is the common factor? Tripping over the cord. What is the variable? The outcome. What causes different outcomes? Luck, circumstances, training…any number of factors will play a part. Safety wants to know about any non-standard events because once they happen, the one extreme event at the top of the pyramid is a statistical certainty. The other, less-severe events alert us to the extremely adverse situation ahead of time.

A real-life example involves birds. There are bird strikes every day, but few can match Capt. Chesley Sullenberger’s Airbus A320 dual-engine flameout and landing on the Hudson River. But this is a rare event compared to the number of non-catastrophic bird strikes.

The Loss-Ratio is also why “No harm, no foul” is never spoken of in Safety Departments. We know that harm is only a short, unlucky step away from no harm.

Several types of reports are available to employees through basic reporting systems. On the reactive side there is a basic occurrence, or event, report. This defaults to an open report where details and identities are visible. The reporting party has the option to select “confidential,” which removes identifying data from the information going to the operational divisions. But all data is open to safety department personnel.

Another report type that should be available is the anonymous report. This removes all identifying information from the report. While these are a necessary part of the reporting system, they are difficult to process. For one, the safety department cannot provide feedback to the reporter. In addition, it is impossible to get any further or amplifying information.

A proactive report should also be available. This is where a person has identified a potential problem and wants to report it before it manifests itself as an accident.

Report formats vary. For example, there can be a single report form with a drop-down feature that allows the reporter to choose which report they want to file. Or there can be a number of different report forms from which to choose.

It is recommended that the safety department call back every single person who files a report. The idea is to thank them for reporting, assure them their contribution is meaningful, gather any additional information and discuss mitigation efforts.

The disposition of reports is fairly straightforward. One flow is listed below. A company can use a number of different tools to identify non-standard events. It might be a reporting system, survey or audit. All adverse events are treated the same. The first stop is the risk assessment. Risk is the product of severity and probability. It is important to estimate those values right away to see if this is a high- or low-risk situation. If it is high risk, then the bosses are notified, and they make a determination as to whether or not the action may continue.

The next step is investigation. There is a temptation to overlook the events that have little or no adverse outcomes. Remember the Loss-Ratio Triangle. Outcome is a function of luck. This occurrence could be a potentially serious event, so the causal factors are identified and mitigated.

There are many investigation tools. Everyone has their favorite. The oil and gas producers, for example, like Bow Tie. Regardless of tool choice, the end goal is the same: Identify and fix the causal factors.

Reports are segregated by operational division and taken to their respective managers or dedicated event report management group. It is their responsibility to develop a corrective action plan. Since it is their department, they have the expertise and authority to make changes. The safety department is not the expert in their affairs and has no authority or responsibility to make changes. What the safety department does is assure that its mandate is realized. That mandate was described in the opening prologue: Identify the underlying systemic issues and assure the responsible department develops mitigation for them.

Safety also serves as the scribe and will document the progress made by the front line, including checks for on-time and effective implementation.

Communications

There must be a parallel communications plan that feeds back information to the front line. News travels fast and employees will be wondering what the company is doing about any serious event. This would include events such as aircraft damage, regulatory action or personal injury.

The safety department should prepare a communique that goes out within 24 hr. of report receipt. This serves two purposes. The first is that it completes the feedback loop. The second, and probably most important, is that it shuts down the rumor mill. This is especially true in a decentralized operation with multiple bases and crews all over the country, if not the world. Good information is hard to obtain in those situations and everyone wants to know what happened. With accurate, up-to-date information, the speculation circuitry goes quiet. Then the event must be followed up with detailed information in a regularly published newsletter.

The newsletter is typically done on a monthly basis, but it can be issued every other month, quarterly or whatever works--just pick a schedule and stick to it. Eventually, employees will come to rely on them for solid, factual information.

Lastly, the accountable executive should be aware of all trends related to the various events and the progress being made by the operational department heads to rectify the non-standard situations. This is often accomplished through a regularly scheduled Safety Advisory Group (SAG) meeting.

Training

The company must give safety management systems (SMS) training to all employees. This usually comes in two parts. The first is a description of the SMS process. This is often based around the Four Pillars. The second, companion piece, describes the way the client manages the SMS program. This would include how to report an event, providing user names and passwords, just culture, feedback tools, and so on.

Next Steps

The next steps could be either a repeat of what is working or exploring new tools. That is largely dependent on the needs and desires of the operation. It may be time for the next, annual, safety survey.

Once the company decides to run a second safety survey, the implementation process is winding down. With the data from the second survey, the trend analysis phase begins. Adding new tools is part of the growth and maturity plan of the SMS. New tools include change management risk assessments, safety risk profile, investigations, audits and any other process or tool that generates hazard information.

Here is one final note. Many of the activities described above are considered “programs.” As was mentioned in the just culture section, this means there is a formal policy statement, roles and responsibilities, SOPs, training, audits and more. The SMS is a program. Others include fatigue risk management, internal evaluation, dangerous goods and more. They all will require significant attention and possible regulatory scrutiny.

The Small Operator

The small operator represents a special case. For example, there is more than one helicopter company out there with a single ship, an owner/pilot whose spouse keeps the books and a “swamper” that is shared among several other single-aircraft operations. In fact, the world demographics for helicopters show that about 85% of all operators have four helicopters or less. About 60% have only one. This data comes from both the Helicopter Association International and Airbus Helicopters. The numbers for fixed-wing companies are likely similar.

For the small operator, the model described above is overkill at best and commercial suicide at worst. So far, there has been no guidance from the authorities about what they expect to see.

One approach is to engage three very responsible tools: one reactive, one proactive and one predictive.

The reactive tool is the reporting system. An electronic system is unnecessary, paper will work fine. One method is to have the solo pilot keep a log of the times they have scared themselves and what they would do to prevent that in the future. Write it down and keep it current.

The proactive effort would be an audit. The audit entity could be the regulator, insurance company, IS-BAO or your best friend who also has a single-ship operation and needs an audit. If you don’t have a regular audit tool, one you can consider is the SMS Evaluation Tool, Version 2, 2019. It is co-sponsored by the FAA, European Union Aviation Safety Agency, Brazil’s National Civil Aviation Agency (ANAC) and several other regulatory authorities.

The predictive tool is the Flight. Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT). While it is senseless to do a FRAT for every bucket drop, one could be done for the morning and one for the afternoon when the wind picks up, the temperatures climb and the density altitude becomes an adverse factor.

Those three actions won’t break the bank, take too much time, or require much outside help. And they cover the full spectrum of the SMS. Again, there is no current advice on what the regulator will want, but this is certainly in keeping with the spirit of the SMS. The SMS is ultimately looking for self and systemic continuous improvement. This simplified arrangement accomplishes that goal.

Summary

There is very little usable guidance in the regulatory material on how to start an SMS program. The process described above works. It sets up the operation for long-term success. But success is not guaranteed. SMS implementation requires thoughtful, deliberate steps. A single misstep in the just culture process, for example, can derail the entire program. Extreme self-discipline amongst management is needed in the just culture arena.

Safety surveys are not flashy. But over time, and with thoughtful subject matter selected, they provide insights into the perceptions of safety and the progress made by the SMS that cannot be replicated with any other tool or process. At one operator, the first-year survey was considered a novelty, if not a little gimmicky. By the fifth year the survey was seen as a critical part of management’s tactical and strategic decision-making process.

The reporting system and all the other information-gathering tools give the safety department the necessary insight into the operation. The different investigation tools with their causal factor focus provide the opportunity to exercise the safety department’s mandate for continuous improvement of the system.

The SMS is often credited, in a broad-brush sense, with providing a successful platform for safety improvement. However, few detailed results are provided. These processes will give you results. Whether they are positive or negative depends on the efforts of the company. In addition, there is even less information available on how to get it done. The activities described above are a proven set of actionable items. They will help the company get that SMS going and set up the operation for success.

Dave Huntzinger, Ph.D., CSP is the subject matter expert in safety for Laminaar Aviation. He has worked in the safety field for over 40 years. A pilot by training, Huntzinger has flown over 50 types of fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft.