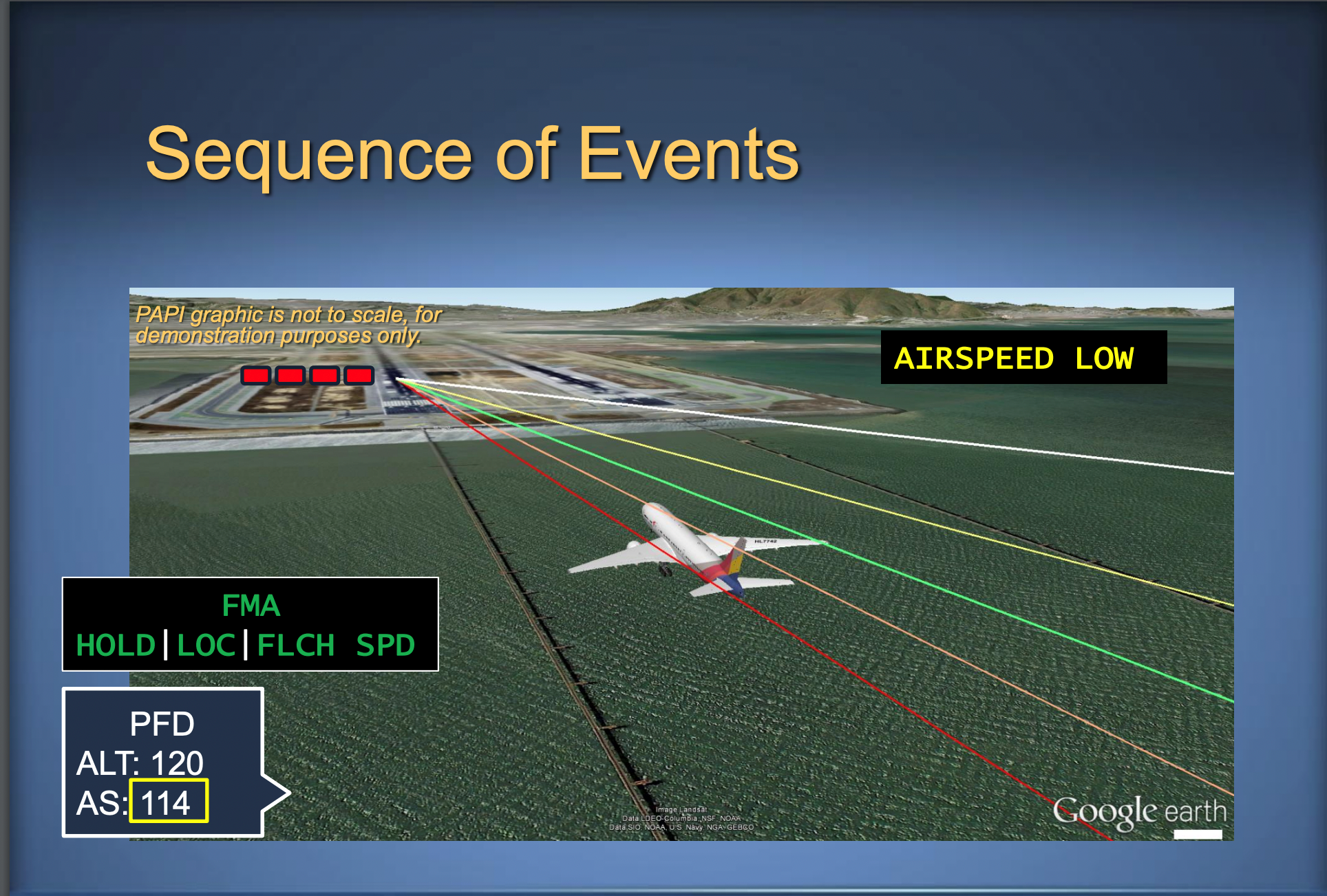

Imagine the shock you would feel when you realize the airplane you’re flying is rapidly descending into San Francisco Bay and it’s not responding to your control inputs.

Your airspeed is sinking, the autothrottle isn’t responding, and you’re pulling back on the yoke with all your strength. Everything you thought you knew about the auto flight system is proving wrong.

That’s what happened to the pilots of Asiana 214 on July 6, 2013.

They’d been led to believe that the autothrottle of their Boeing 777 would “wake up” whenever the airspeed fell below the speed selected on the auto flight mode control panel.

They had 24 sec. after they got below target speed to recognize that the autothrottle was not going to activate, but they were too surprised to react. They didn’t know they had disabled the autothrottle.

They also had a clearance to maintain 180 kt until 5 nm from the runway, and that proved problematic for them. Once they got high, their company policies limited how fast they could descend.

I’ve flown the approaches into SFO many times. It’s a busy place, and they pump a lot of airplanes in and out, often using visual approaches and speed constraints to maximize traffic flow. Getting high and fast is a common problem. As you get close in and are still moving pretty fast, you have to use the speed brakes, get configured, slow rapidly, and drop down to the proper glide path quickly. It’s not a place for rookies, and it’s often a job best done manually.

Asiana’s policy guidance allowed for some manual flying, but in reality, pilots almost always flew with the autopilot and autothrottle engaged. The chief pilot explained in the NTSB public hearing that pilots normally never hand flew the aircraft on approach until below 1,000 ft. By that time the airplane was configured and on speed. All that was required was a little flare. Pilots didn’t even have to retard the throttles--the autothrottle did that for them.

Visual traffic patterns were flown in the simulator but almost never on the line. These approaches were accomplished during training in a standard traffic pattern using timed turns, computed guidance, visual navigation displays, and autopilot and autothrottle on until the simulator was positioned on final approach about 3 nm from the runway threshold.

Many of Asiana’s contract simulator instructors had years of experience. One of them told the NTSB that manual flying was a “big scare for everybody.” He believed that pilots avoided flying manually because if they did something wrong it would be recorded and they would be criticized.

The NTSB interviewed several pilots who had retired early from U.S. airlines and had taken jobs as line captains at Asiana.

They said their first officers were extremely reluctant to fly anytime a manually flown approach would be required. Given the opportunity to turn in to the airport early and make a short approach, they would refuse.

During the investigation, we flew Boeing’s 777 engineering cab in Seattle to try to duplicate the accident flight. It was a nice simulator--no motion, but an excellent visual display. During a break, I invited a group of Asiana pilots to join me in flying the sim around the Bay Area, just for fun.

Returning to the SFO airport, I found myself conveniently lined up with runway 19L. I asked my right seat pilot if he would like to land on 19L and he declined.

So I slowed up, got configured, picked up a gentle 600 fpm descent and flew the sim to a landing on that runway. My colleagues were both shocked and, I think, delighted. 19L was not a normal arrival runway for the company, and trying to land on it might have been a firing offense for them.

The exercise was not just a lark. It was a sincere effort to show that you don’t have to set up the FMC, tune an ILS, and engage an autopilot to fly a simple visual approach.

The constraints that an overly strict automation policy create can inhibit even the most diligent pilots from developing their skills. The FAA now says that even having policies based on automation is the wrong approach.

Policies should be based on managing the flight path. You can use the auto flight system to achieve that flight path, but that system is just a tool. Sometimes you’re better off not using it.