Airbus CEO Warns Sustainability Progress Is Not Coming Fast Enough

Airbus is now also exploring hydrogen fuel cells for its ZEROe project, in parallel with direct hydrogen combustion.

Years ago, Airbus hosted an annual “technical press briefing” for aerospace reporters. They would be put through two days of detailed presentations on current and future programs as well as market and strategy. When the event was over, notebooks were full of material sufficient for several in-depth stories.

But when the aircraft manufacturer hosted its “Airbus Summit” Nov. 30-Dec. 1 in Toulouse and Munich, the contrast could not have been greater. The OEM presented a highly orchestrated multimedia show for more than 100 journalists and influencers, with many more participating online. Videos, sound and light effects, professional stage decoration and a detailed script were used to push a specific message.

- OEM may delay ZEROe service entry if infrastructure lags behind

- New concerns about hydrogen leakage emerge

That message, and the reason Airbus put in such an effort in the first place, was all too obvious: The pressure on the aerospace industry to do more to improve its environmental credentials is intense and likely will only increase. And Airbus is trying to position itself as the driver of the sector’s sustainability efforts, which it may be in some respects.

When the message runs up against reality, things get a little more complicated. Boeing is not in a position to launch any major development program that would result in a more efficient aircraft—likely for some years. Because of that, Airbus has no competitive incentive to move ahead on its own, and engine manufacturers have nowhere to put any new powerplants for the time being. And all of this is holding back any near-term leaps forward.

Most initiatives the sector is launching will likely have medium-term effects at best. Airbus’ signature project, the ZEROe hydrogen aircraft, is not likely to have a material effect on the sector’s carbon emissions for many decades. Whether the most promising roads ahead are instead sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) and hydrogen is largely dependent on progress in other industries—and political decisions.

Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury warned at the summit that things are not moving fast enough. “Ambition is not yet matched by action,” Faury said. “But the clock is ticking. It is difficult to overstate the scale of the energy challenge. The time for excuses is over, the time for action is now.” He indicated, for the first time, that uncertainty about hydrogen supply “could be a reason to delay the launch of the program, even if the technologies for the aircraft are ready.

“I am impressed by how this sector has come together, but overall it is a mixed picture,” Faury said. But he stated that “we need to have 10% of SAF by 2030.” The European Union mandate is for just 5%—and substantially less than 1% of global fuel consumption that is currently covered by SAF. Airbus aircraft are certified for 50% SAF use, with the OEM aiming at certification of 100% SAF by 2030. “We will be leading by example . . . [by investing] our own money,” Faury said.

Much of that money, along with ample French and German public research funds, is flowing into ZEROe. Airbus began by studying three different concepts: a regional aircraft, a narrowbody and a blended wing body. But Glenn Llewellyn, Airbus’ vice president for zero-emission aircraft, all but ruled out the blended wing body. Changing the propulsion system and the basic configuration of the aircraft in one single step would be “too much,” in his opinion. Instead, Airbus is aiming for a classic tube-and-wing concept “with a very different propulsion system,” he said at the summit.

Airbus is leaning toward handling hydrogen storage by putting two tanks behind the pressure bulkhead in the rear of the fuselage. Llewellyn warned that hydrogen aircraft are likely to be more expensive to operate than the cost levels airlines are used to today. “But not disruptively so,” he said. Airbus’ move to explore fuel-cell technology for ZEROe is also strategically relevant for engine manufacturers, and it can no longer be assumed that they are automatically onboard for the project. “But we could easily decide to partner on the engine,” Llewellyn said. Whether Airbus will go with fuel cells or direct hydrogen combustion is a decision for later. “We are not at that stage yet,” Llewellyn said.

Fred Krupp, president of the Environmental Defense Fund, is not even at the stage of wholeheartedly supporting hydrogen-powered aircraft. “Hydrogen can be a good thing, but not necessarily,” he said at the summit. In particular, he pointed to the emerging problem of hydrogen leakage, as well as the lack of standards for both hydrogen and SAF. “We have to make sure that SAF and hydrogen are steps forward, not backward.” He urged the industry to pay attention to the details, which may dictate the initiatives’ success or failure.

“Neither Airbus nor any other company has any equipment to measure [leakage],” Krupp said. But it should be investigated sooner rather than later. Hydrogen is not a greenhouse gas (GHG) itself but does have an indirect climate impact. The water vapor it helps create can form cirrus clouds, which increase global warming.

Moreover, to create water vapor, hydrogen combines with hydroxyl radicals that would otherwise react with methane—which is a GHG—and destroy it, Krupp said. The indirect greenhouse effect of 1 kg (2.2 lb.) of hydrogen is many times that of 1 kg of CO2.

Leakage could come from pipelines, and the farther the hydrogen is carried, the greater the chance of losses. Moreover, the small size of the hydrogen molecule makes it prone to leak.

The issue of leakage was underestimated for natural gas infrastructure until it was measured and understood, Krupp said. The problem should be carefully looked at, Airbus Chief Technical Officer Sabine Klauke said at the summit. Airbus is working on the issue with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and German aerospace research center DLR, she said, adding that “there are technical means to deal with it.”

As governments fund hydrogen projects, “we have to make sure those subsidies go along with leakage measurement,” Krupp said.

Airbus is working on adding catalysts at those places where hydrogen is about to leak, Klauke said. The catalyst causes a chemical reaction with oxygen, thus forming water. Universal Hydrogen, which is developing an ATR 72 hydrogen retrofit, uses such catalysts on its hydrogen modular tanks.

Meanwhile, Airbus is gearing up to start measuring the composition of the exhaust gases downstream in a hydrogen combustion engine. Under its Blue Condor project, the airframer is modifying two gliders with one small engine each. One is being designed to burn conventional Jet A1 fuel and the other one hydrogen, permitting a back-to-back comparison.

The focus is set to be on contrail formation, as contrails generate cirrus clouds. The question to be answered is how two opposing factors play out downstream in a hydrogen-burning engine: the absence of soot (which act as nuclei for the formation of droplets) and the greater generation of water vapor. Nitrogen oxides (NOx) are also to be measured. Instruments will be fitted to a light aircraft that will follow the gliders.

One modified glider has started flying but without the liquid hydrogen system, Sandra Bour Schaeffer, CEO of technology innovation arm Airbus UpNext, said at the summit. Flight testing is planned for the first quarter of 2023.

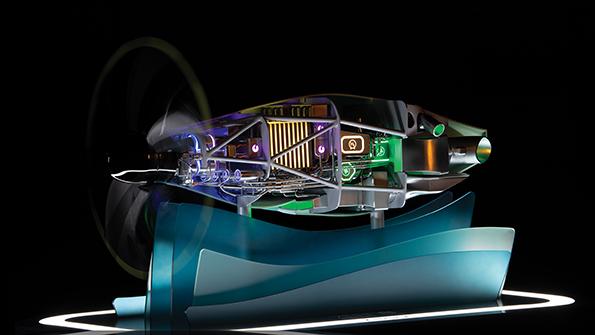

Airbus’ revelation that it will test a hydrogen fuel cell on an A380 testbed comes 18 months after the launch of the ZEROe project and the initial focus on burning hydrogen in gas turbine engines. An engine close to a turbofan was believed to offer a lighter-weight solution and therefore be more suitable for aviation. Airbus now wants to keep all options open, especially as a fuel cell may have less climate impact overall.

The 2.1-megawatt engine, resembling a conventional turboprop, is planned to be fitted on an upper-fuselage wing stub that is also being designed to test a GE Passport as part of a joint effort with CFM. The fuel cell engine test campaign is scheduled for the same period, 2026-28.

Both technologies use liquid hydrogen and are being explored in parallel, Llewellyn said. “At scale, and if the technology targets were achieved, fuel cell engines may be able to power a 100-passenger aircraft with a range of approximately 1,000 nm,” he added. “We are giving ourselves additional options that will inform our decisions on the architecture of our future ZEROe aircraft, the development of which we intend to launch in the 2027-28 time frame.”

A hydrogen fuel cell and the associated electric motor and propeller are expected to be more efficient than burning hydrogen in a gas turbine. Other benefits include the absence of NOx (which is suspected of contributing to global warming) and an even lower probability of forming contrails, which are known to play a role in global warming.

The test engine is being put together in Hamburg, Germany. It has been assessed at subsystem level, as the electric motor is still being tested.

Airbus has been cooperating with fuel-cell specialist ElringKlinger. In 2020, the two companies created a joint venture, Aerostack. The fuel cell in the test engine uses an arrangement that puts together cells into stacks, and the stacks into four so-called channels, making the layout scalable.

Before installation on the A380, full engine evaluations will take place at Airbus’ E-Aircraft System House ground-test center in Munich.

For the test engine, the Hamburg team kept subsystems segregated for better accessibility. Engineers came from the company’s space division—to take advantage of their skills in batteries—and Airbus Helicopters, for the gearbox that will link the motor and the propeller.

The biggest challenge will be weight. One should look at the full equation, factoring in the better efficiency, Hauke Luedders, head of fuel-cell propulsion systems for zero-emission aircraft, said at the summit.

Comments

* Current lithium batteries are 50X heavier than jet fuel

* By 2030 solid electrolyte lithium batteries could be only 25X heavier

* That could increase battery range from 450 miles to 900 -- inadequate

* Sustainable aviation fuel SAF emits carbon -- questionable to Greens

* Green hydrogen is the only path to reach 2,000 miles or more range

* With no carbon emissions

* The round-trip efficiency of hydrogen from solar or wind is only 25% to 50% with electrolysis at 40% to 70%, fuel cell at 80%, compression at 85%

* Burning the green hydrogen in a turbine engine is considerably worse

As you say, not good. But no better alternative has been discovered.

Sigh.